|

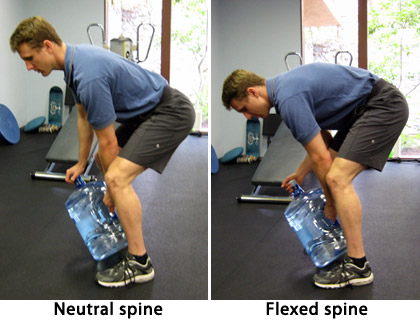

10/31/2013 1 Comment Backbend Fundamentals Note: Contraindications to back bends are spinal stenosis and spondylolisthesis. Backbends are a great part of any yoga practice. This is for several reasons. Traditionally, back bends are used to open the chest in preparation for pranayama (breathwork). From a chiropractic stand point, it is a counter movement to the postures we are of are guilty of sitting in for too long. What posture am I talking about? The one we see most often when one is sitting at a desk for long periods. Slouched with shoulders rounded forward. If a lot of time is spent in this position, the underlying tissues involved under go deformation. The intricate posterior tissues of the spine, such as ligaments and interspinous muscles undergo a lengthening and weakening in structure- a phenomenon known as “creep” (not like the radiohead song). In an adaption to this posterior lengthening, the pectoral muscles in the chest undergo shorting, which further reinforces this bad posture. Back bends act to counter this type of position. They focus on shoulder opening and thoracic extension, taking the constant strain away from these tissues. Back bends should be challenging, but comfortable. This is not the case for your average yogi. This article breaks down the backbend in the hopes of making the backbend more restorative for all who encounter difficulties. Usually there are two types of people who finds difficulty with back bends: those with tight muscles and ligaments, and those who are naturally loose and highly flexible. The ideal candidate is someone in between. There is an idea in health that the more flexible you are, the healthier you are. However, a hyperflexible person is more prone to ligamentous injury due to a loss in stability. Interestingly, hypermobile people tend to have tight hip flexors (psoas muscle), but compensate for this with over extension of the low back. The psoas muscle originates on the anterior aspects of the lumbar spine extends downwards merging with iliacus and inserts on the upper inner aspect of the femur (thigh bone). If this muscle becomes tight, it pulls the lumbar spine towards its inferior attachment, thus increasing the curve of the low back and compressing all the lumbar joints (facets). Core strength is also usually lacking in hypermobile individuals, so they tend to hinge at one segment in the lumbar spine over and over again rather than achieving more even extension throughout the spine. Because of this, its most important for these individuals to focus on stability and strengthening. They also should consider backing off a little in search of even extension rather than maximum depth of the pose achieved by a few vulnerable segments. To prevent jamming in the lower back and neck, bring your awareness to the spine as a whole. It is important to visualize a smooth curve throughout the spine, where each segment produces an equal amount of extension. Granted, anatomically it is impossible to have equal extension through every joint in the spine; however, just the added awareness will help you extend with greater care and integrity. Focus on promoting extension in the areas of the spine that aren’t already overworked. This brings us back to the thoracic spine. Though the ribs and the orientation of the facets, make extension more difficult in the thoracic spine, focusing on drawing the shoulders back, lifting the chest and depressing the shoulder blades down the back will help you maximize extension here. Those that are stiff and less mobile, commonly have a decreased range of motion in the chest, shoulders and hips. The mechanism of this has been previously discussed with regard to poor posture. These individuals therefore, need to work on flexibility more so than strength and stability in preparation for back bends. Shoulder opening postures and pectoral stretching is a good start. Finally, the most important principle in performing an effective and safe back bend is that the strength of the posture is actually derived from the legs. Lets take cobra pose for example (seen below). When I first started yoga, I thought I was supposed to be simply pushing my upper body off the ground with my arms to passively extend my back. Needless to say, I found back bends very painful and thought they were bad for me because I was jamming my joints. In the proper teaching of a back bend, it is essential to emphasize the importance of firing up the legs first. In cobra pose I like to tell my students: “ground the tops of your feet into the mat as you fire up the legs, feeling the knee caps lift off the floor. Engage the inner thighs and focus on turning them inwards so the tailbone can descend toward your mat.” This descending of the tailbone is part of what helps create length in the spine as you extend, preventing the joints of the low back from jamming. It also takes pressure off the segments we tend to overwork in this posture. As a chiropractor, at first I was confused as to why we’re not told to fire up the glutes, because they are our primary hip extensors and hip extension is an integral part of a backbend. However, when you fire up your glutes, you externally rotate the thighs and make it difficult to create length in the spine by letting the tail bone descend. Also, by internally rotating the thighs, the hips are moving towards a closed packed position, which is more stable. That being said, I do promote use of the glutes in a backbend, however, at about 50% maximum contraction so the internal rotation of the thighs can still be maintained to some degree. My reasoning for this is that many people with chronic back pain have hip extensors that are weak or lazy, causing the extensors of the spine to compensate for a motion they aren’t designed for. Telling people to turn off their glutes for hip extension promotes a faulty motor firing pattern like the one I just discussed. Think more of using the inner thighs and allowing the tailbone to descend and the rest will come. In summation, when you do to do a backbend remember: 1. Keep the spine long, focusing on distributing extension throughout the spine instead of overworking a few segments. 2. Fire up those legs. Without them, your foundation is lost and the posture can no longer be done safely. 3. Open the chest and draw the shoulders back. This will not only help you increase extension in the thoracic spine, but will improve your pranayama (breath). Additionally, it will stretch out the pectorals and release the tension on the passive structures of the back. 9/13/2013 0 Comments Safe Yoga Principles: 2 &3#2 Form before Depth |

|